By Rita Brhel, managing editor and attachment parenting resource leader (API)

Like many new parents, I naively believed that once I got past the first few years of physically intense infant and toddler care, that surely the rest of childhood would be comparatively easy. By the time my third child came along, I learned to relish those early years. Children don’t get easier to raise the older they get, and they don’t necessarily get harder either. Every age and stage has its own joys and challenges.

Like many new parents, I naively believed that once I got past the first few years of physically intense infant and toddler care, that surely the rest of childhood would be comparatively easy. By the time my third child came along, I learned to relish those early years. Children don’t get easier to raise the older they get, and they don’t necessarily get harder either. Every age and stage has its own joys and challenges.

One of the challenges I’ve encountered lately that has really made me think has been my five-year-old daughter’s tendency to lie. My four-year-old is an expert storyteller but she tells wildly imaginative, make-believe stories to entertain (“and there was this octopus and it stood on the barn and ate cheese”) and will readily tell the truth if asked. My five-year-old, on the other hand, tells stories to try to get her sister in trouble. Not that it works. I’ve maintained since the beginning that I value truth-telling, even when the child is admitting a wrong. So, say, my daughter breaks a lamp and she tells me what happened truthfully, I look beyond the broken lamp and value the trust that’s there. I don’t react negatively; we just clean it up. But, the problem is when a child blames her sibling and her sibling blames her sister; there is no punishment, but we have to spend a lot more time talking and trying to figure out what the whole story is. I still don’t react negatively, but lying is something that concerns me because it violates my trust. I see it as a sign of a relationship issue. I give a reminder as to what lying is and why we don’t lie to one another, and ask questions to see if there is indeed a relationship issue such as that my daughter feels that I don’t give her as much attention as her sister or if she feels hurt by me for something earlier in the day. It seemed, though, that this wasn’t ever the case; my five-year-old daughter would say all was good, that she wasn’t sad or mad, but she continues to try these lies.

I pondered how my five-year-old learned this behavior for the longest time. I could not understand how she conjured up lying to avoid getting into trouble when being in trouble at our house doesn’t mean anything upsetting. The punishment she seemed to be trying to avoid, by the fear I could see in her eyes, never materialized. She would leave the conversation happily, skipping off to her next play activity. But, before long, we were talking about lying again. Puzzling.

Then, a mother whose child goes to the same preschool suggested that my daughter was learning the behavior at school – that some of her playmates lie to avoid punishment in their homes and were bringing that behavior into the classroom. My daughter was likely just trying out a behavior learned from her friends. This makes sense, as I’ve seen my daughters playing that they were putting their dolls into timeout when we do not use timeout in this family. And we’ve gone through phases when both girls were saying questionable words like “darn” and “stupid,” again words not spoken in this family.

But this lying “phase” has persisted more than a few weeks, and I was beginning to wonder if my approach was developmentally appropriate or if there was something more I could do. Fortunately for me, I didn’t have to wait long before I got an answer. Recently, parenting educator Patricia Nan Anderson, PhD, of Seahurst, Washington USA, held a teleclass on this topic, expanding also into cheating and stealing.

Celebrate Lying?

I have heard from some parents and parent educators alike that lying should be celebrated in a way, because it signals that the child has reached an appropriate developmental milestone. I’m not throwing a party, but this does mean that parents don’t have to fear lying as the basis of future juvenile delinquency. Lying is normal and a sign of positive brain development.

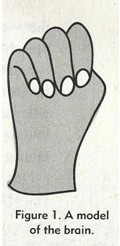

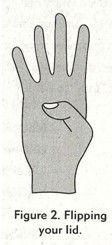

“Once a child understands that others have thoughts of their own, they understand that others can do something on purpose but also that things can happen accidentally,” explained Anderson. This ability doesn’t happen until at least age four. Somewhere between age four and seven, depending on the child, guilt and shame develop. And that’s when children are able to lie.

Furthermore, the ability to delay personal gratification, otherwise known as patience, develops by age two in some children but not until age eight. This plays into why some children have the propensity to lie more than others.

Lying, as well as cheating and stealing, in children older than age nine may be a sign that the child feels powerless on her own. Parents can help the child empower themselves.

“All of this stuff is normal,” Anderson said. “Every parent encounters these behaviors. Every child has a normally over-developed sense of greed and a normally under-developed sense of ethics. Your job is not so much to squash the bad thoughts than to strengthen the good thoughts.”

How to encourage moral development:

- Model moral choices out loud – This is more than leading by example, which is important in itself; this is talking to your children about your thought process in making choices. Children see their parents as perfect, never tempted and never making mistakes, Anderson said. They need to know that you, too, have to play tug-of-war between greed and ethics. For example, say you’re eating cookies: While you’re dividing the cookies among you and your children, say out loud “Mmm, I love cookies. I could eat all of these cookies myself, but I love each of you and want you to have a cookie, too.”

- Analyze media-based dilemmas together – This not only pertains to managing screen time or discerning which media programs to view or games to play or books to read, but also to discuss what is going on with characters’ choices in the story plot. For example, say you’re watching a TV show about the three little kittens that lost their mittens: “Oh, those kittens are so sad that they lost their mittens. And when they told their mother, she said they couldn’t have any pie. Oh, that makes them sad. What do you think they should do?”

- Ask the child’s opinions about moral dilemmas – This isn’t a guess-what-Mom’s-thinking exercise, Anderson said; there isn’t one answer. Parents can use the child’s answer as a clue to his current moral development. For example, say your son and daughter are arguing over a toy: Ask each of them “What do you think you should do?”

- Celebrate your child’s good moral choices – This is just as it sounds. Recognize your child when she makes a choice that aligns with your family values.

Discipline for Lying

Guilt and shame are two of the most uncomfortable feelings that a person can feel, and lying is a natural reaction to not feel guilt and shame, said Anderson, as well as to avoid punishment. But, by viewing lying as part of normal development, punishment doesn’t have to be the rule. How to respond positively to lying:

- Never try to catch your child in a lie – If you know the truth, don’t act like you don’t. This only sets him up to lie. And if you don’t know the truth, phrase the question differently: Instead of asking “Who broke my lamp?” say “I see that my lamp has been broken. Tell me about that.”

- Never punish your child for telling the truth – Parents who practice Attachment Parenting strive not to punish for any reason, but it’s especially important not to react negatively to a child telling the truth, no matter what that truth is. This is especially important with older children and teens, said Anderson.

And what if your child does lie? Positive discipline techniques depend on the child’s age and development, explains Judy Arnall, parenting educator from Calgary, Alberta, Canada, in her book, Discipline Without Distress.

Preschoolers, ages three to five, are typically just learning the difference between reality and fantasy. This age group doesn’t so much tell out-right lies than use story-telling to explain their wishes. Parents can help preschool children by teaching them how to get their needs met without lying, as well as reading books about lying. Anderson’s advice in rephrasing questions is helpful, too. Instead of asking “Did you take that toy from John’s house?” say “I see you have one of John’s toys. We need to give it back.”

Children age six to 12 lie to avoid consequences or to fit in with peers, said Arnall. Teaching by example is important in this age group, as is teaching problem-solving to get needs met. She agrees with Anderson to never punish for truth-telling, no matter what the truth involves. She emphasizes for parents to avoid labeling and over-reacting, but also to avoid dismissing the behavior. Telling the child that while telling the truth can be hard, you appreciate it and reassure the child that he won’t be punished for it.

With teenagers, Arnall advocates being straightforward. Parents should continue not punishing for truth-telling and to teach problem-solving for the original issue, but I-statements are effective in communicating why lying is not acceptable, such as “I’m upset when I’m not told the truth. I find it hard to trust you.”

Put It in Perspective

Parents often fear that lying is a sign of a larger psychological problem in their children. In a small percentage of children, there is a pathological reason, but this is rare; Anderson advises parents to only consider it if your child’s behavior appears compulsive. For the great majority of children, lying is simply a normal part of growing up.

“Think of the times you were tempted as a child or now,” Anderson said. Virtually every person has told a lie at one point in their life. Lying may be morally wrong, but it’s common. Be understanding of your children.

Cheating

Cheating happens because winning feels good. While cheating can be done with the intention to deceive, children typically resort to cheating simply as a way to level the playing field, Anderson said – when she feels at a disadvantage, is frustrated with the situation, and feels in need of an accommodation. Think of a younger child playing a game with older siblings. How to respond positively to cheating:

- Provide your child a script to opt out of an activity when tempted to cheat, without admitting that he finds the game difficult, such as “I’m not having fun, so I’m going to go do something else.”

- If your child cheats on a school exam or assignment, talk to the teacher about it being a sign that your child is frustrated with the material.

Stealing

Stealing in children age eight or younger often occurs when a child is seeking boundaries, during which she steals something in plain sight or tells you about taking something, or as a result of poor impulse control. With a younger child, it could be a misunderstanding of what it means to borrow. Parents should view stealing in these years as an exploration of relationship rules, and to react by explaining the rules for each incidence.

It’s when stealing becomes intentional that parents need to take notice, said Anderson. Children who are at least nine years old may use stealing as a way to fit in with his peers, to boost self esteem, on a dare, as a form of revenge, or as recreation. Children don’t develop the full ability to consider the consequences of their actions until their late teens, so if your child is stealing intentionally, the first step to resolving it is to figure out why. Second, parents should use the event to teach family values.

“The question should not be, ‘Are you mom enough?’ The questions should be: