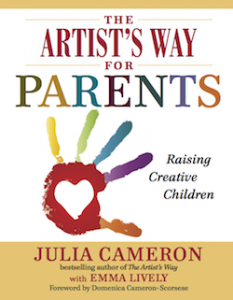

The Artist’s Way movement began more than two decades ago as author Julia Cameron shared her ideas with a few friends in her living room. Since then, Julia’s instruction through books and courses has helped millions of people around the world discover–and recover–their creativity, including parents.

About the Interviewer

About the Interviewer

Lisa Lord lives in Dublin, Ireland, with her husband and two children, where she works as an editor for Firecrest Clinical. She serves as the Assistant Publications Coordinator for Attachment Parenting International (API).

Julia lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA. She is the author of 30 books, both fiction and nonfiction, including The Artist’s Way for Parents. Whether you are new to her work or have a bookshelf filled with years of your Morning Pages, whether you are an aspiring blogger or simply wishing to experience more creativity in your parenting, Julia shares inspiration appropriate for every family.

Julia lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA. She is the author of 30 books, both fiction and nonfiction, including The Artist’s Way for Parents. Whether you are new to her work or have a bookshelf filled with years of your Morning Pages, whether you are an aspiring blogger or simply wishing to experience more creativity in your parenting, Julia shares inspiration appropriate for every family.

Julia’s tips fit specifically within API’s Eighth Principle of Parenting: Strive for Balance in Personal and Family Life as well as API’s Seventh Principle of Parenting: Practice Positive Discipline.

API: In your work, you talk about creativity as a spiritual pursuit. What do you mean by this?

JULIA: I have been teaching for about 25 years, and I have found that as people work on their creativity, they wake up to their own spirituality.

JULIA: I have been teaching for about 25 years, and I have found that as people work on their creativity, they wake up to their own spirituality.

When they use the tools of paying attention and Morning Pages, it’s actually a form of prayer. In this way, they come to feel that they have a benevolent connection with a higher power–or the universe, the Tao, the force, it doesn’t really matter what you call it.

When we work on our creativity, we find ourselves feeling guided. In the actual moment of creating, we find that we have a sense of something larger than ourselves guiding us.

In working with creativity tools, people are building a spiritual radio kit.

API: What are the greatest benefits of parents tapping into their own creativity in parenting, in terms of the parent, the child and the relationship?

JULIA: When you pay attention to the creativity of your child, you are connecting to a part of your child that is timeless.

When you try to connect to your child’s creativity and sense of wonder, you reawaken your own creativity and your own sense of wonder.

So if you focus on making it a safe and benevolent environment for your child to have self-expression, you then find yourself with a desire to have a safe, protected environment for yourself. The home becomes a sort of sanctuary, not only for your child’s creativity but for your own.

API: It seems that the very intention to foster your own creativity and your child’s creativity brings more connection to parent and child as well.

JULIA: Yes, they form a very special kind of bond. The children appreciate this sense of safety that the attentive parent gives them, and the parent appreciates the whimsy and originality that comes forward from the child.

API: It’s not uncommon for people to feel, “Oh, I’m not creative.” Why do you think so many people feel this way and what effect might it have on their lives?

JULIA: I think we have a mythology around creativity that is very destructive. We tend to believe that only a few people are genuinely creative, that they are born knowing they are creative and that they go through life with that creative spark undimmed.

We need a new mythology around creativity, one that says we are all creative, we all have a divine spark within us, we all have the capacity to tap into our originality and we all have gifts whether we recognize them or not.

When you start using just a few simple tools like Morning Pages and Creative Expeditions, you begin to wake up to your own thoughts and impulses.

API: You offer 3 basic tools for a foundation as parents begin to explore their creative impulses. Can you tell us about the first one, Morning Pages, a tool you recommend to all of your students and readers?

JULIA: Morning pages are 3 pages of long-hand morning writing about absolutely anything. I assign them to anyone trying to wake up their creativity. What they do is clarify, comfort, cajole, prioritize and synchronize the day that you’re going to have.

As you lay out on the pages your secret thoughts, you begin to become more authentic and you begin to know yourself much better.

API: Why might Morning Pages be especially useful for parents, the very ones who may feel they do not have the time or energy for writing?

JULIA: A lot of times Morning Pages are extremely important for parents, because we have a lot of emotions about taking care of our children that we feel we shouldn’t be having. We may feel resentful, lonely, angry and frustrated.

If you get those feelings down on the page, it’s as though you are confiding them to a greatly listening friend. You begin to take comfort. You begin to have ideas about what you can do differently in order to feel more connected to your child, more connected to the universe, more connected to the idea that your child is connected to the universe and so on.

It’s just very important.

API: What do you say to parents who feel they can’t make time for Morning Pages? Are there alternative ways to fit them into busy lives?

JULIA: A lot of times people think they don’t have time for Morning Pages. I will tell them to just take a dash at the page, get as much done as you can, then as you settle into your day’s routine, sneak in extra writing time until you have your 3 pages completed.

API: Tell us about the second tool, the weekly Creative Expedition, during which parent and child together plan a fun weekly outing.

JULIA: It doesn’t have to be high art. It’s just an expedition that intrigues you. You might to go an aquarium store. You might go to an art gallery, though you probably wouldn’t when your children are small.

You take this expedition, which bonds you further with your child but also gives you an end to claustrophobia. We need to have expeditions outside of the house where we interact with other people.

API: The third basic tool is Highlights. Can you tell us about that?

JULIA: Highlights are a nightly ritual, which may be done before or after reading to your child, when you single out the high point of your day and share that with your child, then ask the child to do the same.

This builds a habit of optimism and of gratitude.

You may find that it’s a genuine spark of connection, because the same thing was a highlight for both of you, such as when you took your dog to the dog park and watched the puppies playing.

Other times your Highlights may be very different, and you get to know your child’s unique personality through listening to the Highlights.

API: You also recommend walking as a creativity tool. How does that work?

JULIA: Very often, when you walk out with a problem and you walk for 20 minutes, you may find yourself walking back in with the solution. Walking helps integrate the insights you receive from the other tools.

It’s wonderful to put yourself in touch with nature, even if nature is just looking at the window boxes in the neighborhood. You also put your child in touch with nature, and this leads to a sense of connection.

API: These tools are ways to create rituals, and you encourage people to incorporate other rituals into their lives, as well. What are the benefits of rituals?

JULIA: What we are talking about is creating a sense of safety. Rituals bring a sense of safety to the child and to the adult. As you pause and perform your daily ritual, whether it’s grace before meals, a bedtime prayer or sharing Highlights with children, these rituals tell them that there is safety in the world.

API: In terms of creativity, I would imagine that bringing a sense of safety for yourself, with ritual or the other tools, perhaps means your mind is less occupied with worrisome thoughts, which opens the door for even more creativity because you have a freer channel to connect with your creativity. Do you feel that’s the case?

JULIA: I do.

API: You say “the act of spending time doing something we want to do as opposed to something we have to do takes courage,” and you encourage parents to include enjoyable activities in their day, even if only for 15 minutes. Why is this so important?

JULIA: Children learn from what they see us doing. They learn when they see us valuing ourselves.

In the book [The Artist’s Way for Parents], I gave the example of an editor who felt he had no time to read his favorite classics, because he was so busy being a parent. He loved reading, so I suggested he read for 15 minutes a day. He said he didn’t have 15 minutes, so I asked him to just try.

He tried reading a book that he loved, Moby Dick, and his son noticed he was reading and asked him about it. They began to have a conversation about the book. About a week later, he found his son sitting in his reading chair with a book. When the father asked about the book, the son said, “Oh, Dad, it’s another book about a whale—Pinocchio!”

API: You feel that structure and limits lend themselves to creativity. Can you tell us about how to use structure with time to create freedom and creativity?

JULIA: We often think in our mythology that creativity demands great swathes of free time, and we don’t have that.

Instead, I have found that if you have a careful structure that allows for some play time and allows for your child to unwind, then they can turn to their homework or to their lessons with a renewed sense of self. When you have scheduled free time, the child is willing later to turn to lessons and what we might think of as self-improvement.

API: Our technology-filled lives often don’t leave any room for boredom, which you define as “being ready for the next idea.” Children and parents alike may be almost constantly stimulated by technology in one form or another. What impact do you feel technology has on our willingness to be bored and therefore on our creativity?

JULIA: I think that when we say we’re bored, what we’re doing is actually a manipulation. We are saying, “Fix it for me.”

If you resist the impulse to meddle and instead say to the child, “I’m sure you can figure out what you want to do next,” then it imparts to the child a belief in their own resiliency and their own originality.

If you suggest that together you spend an hour without any screens, and you put your own phone aside and don’t go near your computer, then you find yourself coming up with new ideas.

In the book [The Artist’s Way for Parents], I talk about a child who was so over-scheduled by his mother’s determination that he be the best and brightest. I suggested to the mother to give him an hour’s free play with no screens. And when she did this, he picked up a pen and started writing a short story.

API: Speaking of education, our children’s current learning culture outside the home is often based on test results, where there is always a right and wrong answer. Can you talk about the effects of this on creativity?

JULIA: I want to say you should hang tough!

What happens is that when kids turn about 7, they start to be given standardized tests [in public and private schools], and the focus of the classroom becomes how well they do on the tests. It teaches children that what matters is not the process of learning, which is where creativity lies, but the product, which is the test result.

The emphasis on testing well means that the focus is on performance. It’s very competitive. Originality is not valued. Spontaneity is not valued. What is valued are rigid responses.

I think parents sometimes fall into the trap of believing that they have to make their children test-worthy, and they reinforce in their children beliefs in the rigidity of responses.

What I would say is you need to create an environment where there is an appreciative response for creative thinking. If this doesn’t happen at school, that is all the more reason for it to happen at home.

API: Can you talk about process versus product and how this contributes toward creativity?

JULIA: Creativity is the art of making something out of nothing, the art of making something new out of something old. It’s a moment-by-moment action in which you become entranced with your own imagination.

Our job as parents is to appreciate the process that our children go through rather than trying to correct it into a more rigid form. For example, if you have a child who makes a green pony, you say, “Oh a green pony, that’s wonderful,” instead of telling the child ponies aren’t green.

API: So judging and making statements about something being right or wrong, good or bad, are not necessarily helpful. Nurturing the child’s interest and appreciating whatever the product is would be far more helpful, so the child comes to enjoy the process?

JULIA: Yes, that’s it.

API: Can you talk about the danger and futility of seeking perfection, whether it be in our endeavors or our children’s, our bodies or our physical surroundings?

JULIA: Perfectionism is probably the biggest creativity block I run across. When we speak of perfection, we actually are reaching for an unattainable goal, because as human beings, we aren’t perfect.

If we look to perfection to judge our work by, we will always fall short. So it’s very important to model that it’s OK to be imperfect and that there are such things as rough drafts.

For children to realize that practicing imperfection over and over again is moving a little bit at a time toward an ideal, is a much kinder way to go than demanding that the first job or the first attempt be perfect. That can stop a child’s or anyone’s creativity in its tracks.

API: What effect can a gratitude practice have on our experience of daily life, our interactions with each other and our overall creativity?

JULIA: Gratitude is a form of optimism. I have people write out gratitude lists of things that they feel are right with their life, and very often, it creates a complete shift in focus.

Before it, we may be grumpy or feeling sorry for ourselves and generally negative. When we try to practice gratitude, then instead of saying, “My house is too small and messy,” we might say, “I have a snug house with a secure roof, and I can work at decluttering it and making it more liveable.”

We often have so many things to be grateful for, and it’s particularly true in our human relationships. We may focus on what is wrong, but then we realize, “Gee, my husband really has a wonderful sense of humor.”

API: So with our children, stopping to take a minute to be grateful for all of their good qualities changes things right there and then in that moment. It allows us to look at them completely differently.

JULIA: Yes, that’s right.

Creativity Tools from The Artist’s Way for Parents

-

Heightening Downtime–List 10 “frivolous” things that make you happy but that you believe you no longer have time to do, such as cooking for yourself, listening to classical music and knitting. Now choose 1 of these things. This week, spend 15 minutes a day indulging in it. Fifteen minutes is a lot more than no minutes—and 15 minutes is enough.

-

Modeling Imperfection–Fill in this blank 5 times: “If I didn’t have to do it perfectly, I would try ___________.” Try modelling imperfection for your child. Choose something you know you will not do perfectly and allow your child to witness this. Now ask your child, if she could try any creative activity she’s never tried before, what would it be? See if you can devise a way for her to take a small step into the realm she mentions. Allow yourself—and your child—to be imperfect as you work with this exercise. You are after fun, not finesse.

-

Grateful for Gratitude–Both you and your child will benefit from expressing gratitude. Together, take turns naming 1 thing you are grateful for. Gratitude relieves pressure, and this exercise will naturally restore emotional balance. Choose 1 item you named and ask your child to do the same. Now make a “creative offering,” referencing the thing you are grateful for—draw a picture of it, write a song about it, make up a poem. As you and your child share your offerings with each other, you cherish and honor that which you are grateful for.

From The Artist’s Way for Parents by Julia Cameron with Emma Lively. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2013.