Our experiences are what make each of us who we are. We are all unique. While many of us may go through the same experiences as another, no two people process each event in our lives the very same way. Some people come away from a challenge in their lives empowered to help others.

About the Interviewer: Rita Brhel, CLC, API Leader, is the Publications Coordinator and Managing Editor for Attachment Parenting International (API). She lives at the edge of Fairfield, Nebraska, USA, with her husband and their 3 children, on a sustainable farm. Rita is also a freelance writer and a WIC Breastfeeding Peer Counselor.

Meryn Callander of Victoria, Australia, did just this. She began her career in social work in Australia before heading to Europe and then the United States, where she met John Travis, MD, known as the father of wellness. She and John joined forces furthering the wellness movement. Then, in 1993, Meryn became a mother — an experience that gave her a whole new perspective on wellness in how profoundly childhood impacts the well-being of adults.

Meryn Callander of Victoria, Australia, did just this. She began her career in social work in Australia before heading to Europe and then the United States, where she met John Travis, MD, known as the father of wellness. She and John joined forces furthering the wellness movement. Then, in 1993, Meryn became a mother — an experience that gave her a whole new perspective on wellness in how profoundly childhood impacts the well-being of adults.

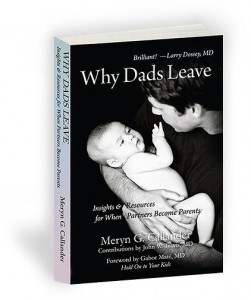

In 2012, Meryn wrote Why Dads Leave: Insights and Resources for When Partners Become Parents, with contributions from John. The book grew out of Meryn and Travis’s parenting journeys, compelling them to identify and explore the dynamics underlying the epidemic of men disappearing from their roles as fathers — whether physically or emotionally — soon after the birth of a child, and to provide tools to keep couples growing together rather than apart as new parents.

In 2012, Meryn wrote Why Dads Leave: Insights and Resources for When Partners Become Parents, with contributions from John. The book grew out of Meryn and Travis’s parenting journeys, compelling them to identify and explore the dynamics underlying the epidemic of men disappearing from their roles as fathers — whether physically or emotionally — soon after the birth of a child, and to provide tools to keep couples growing together rather than apart as new parents.

I found the book to be one of the most eye-opening resources to be created for new parents, particularly with the focus on the “dynamic of disappearing dads,” which I explore in this interview with Meryn.

API: Thank you, Meryn, for your time. Please begin by sharing your background in the wellness movement.

MERYN: Well, it began in 1978. I was living in Australia and read of John Travis, “father of wellness.” He was talking about health being more than physical — that there were also emotional-mental and spiritual dimensions, and our “wellness” was, in large, our own responsibility.

I was a social worker and working with children in crisis at the time, and I took to the term “wellness,” which at that time was virtually unheard of. I felt like I was applying Band-aids, never addressing the real issues that led these children into crisis — and could lead them out. This idea of personal responsibility seemed to be taking the “reality therapy” approach we were using with the children at the time, a layer deeper. So I decided to learn more about this thing called wellness.

I traveled to the [United] States to attend a residential seminar with John at the Wellness Resource Center in California [USA]. That led to marriage that spanned over 30 years and professional partnership. Over the years, we moved our focus of wellness beyond the personal, to look at what was asked of us in developing authentic and collaborative connections with others.

We were always surprised seeing the struggles even people involved in the psychological and medical fields who joined our network, had in developing intimate and trusting relationships. Ultimately, that led us to Jean Liedloff’s Continuum Concept. Now we saw that the core of wellness was in how we raised our young!

Having focused for years on adult wellness, this discovery felt like a huge break-though. We saw that the wellness of an individual — of families and the planet — is inseparable from the way we raise our children.

API: Your book, Why Dads Leave, is amazing. How you were introduced to advocating for emotional support of new parents, particularly fathers?

MERYN: At 40 years of age, I wanted a baby — a continuum baby, of course. Now we took up the cause of what we soon discovered was known as Attachment Parenting. I began the Wellspring Guide, a quarterly publication featuring in-depth synopses of parenting books.

In 1993, our daughter Siena was born at our home in the hinterland of Mendocino County [California, USA]. In 1999, along with 11 other experts in the field of birth and child development, John and I cofounded the Alliance for Transforming the Lives of Children — a wonderful experience, a “new family” and another story.

Well, we had a planned conception, a carefully tended pregnancy and home birth. We thought we were so prepared for this adventure in parenting. Initially it was incredible and so exciting! We were both so much in love with this little being and the joy she brought into our life.

As the months went on, John got increasingly depressed. He had struggled on and off with depression all his life, but now it was happening more and more often. I oscillated between being sad and disappointed, and being angry at his withdrawing from us. When he wasn’t depressed, he was great — unwavering of his support of attachment practices, and a loving and playful dad to Siena. But it was so hard when he was depressed. And he was going longer and deeper into this pattern of depression and withdrawal.

It was some years before Jack began to understand what was happening and wrote “Why Men Leave,” a 2004 magazine article that was published in the United States and Australia. It generated such a strong reader response that I felt compelled to dive wider and deeper into the dynamics underlying our experience — and eventually to write Why Dads Leave [the book].

Of course, I had no idea what I was getting myself into when I began writing. I discovered layer upon layer of factors — personal, interpersonal, political and cultural — driving what we had termed Male Post Partum Syndrome (MPAS) and the dynamic of disappearing dads.

API: Please explain male post partum syndrome and the dynamic of disappearing dads?

MERYN: As your readers well know, a secure mother-infant bond is fundamental to a child’s well-being. Discoveries in the field of neurobiology confirm that a secure mother-infant bond depends on many factors:

- A natural birth

- Breastfeeding

- Near-constant physical contact through carrying infants in-arms or in slings

- Cosleeping

- The recognition that babies are social beings who thrive on loving connections.

Of course this is what Liedloff discovered and many indigenous cultures have always known.

Now put this together with the fact that most everyone in the Western world born since the 1930s has been subjected to modern child-rearing practices that interfere with secure attachment:

- High-intervention birth

- Artificial baby food

- Pushed about in wheeled carriers rather than carried on the body in slings

- Left to “cry it out”

- Left to sleep alone.

Now here is the piece of the puzzle that many people practicing — and advocating — Attachment Parenting are not aware of. These little boys grow up to be men looking for the mommy they never connected with. Time comes they believe they have found her, marry her and everything’s looking fine — until baby comes along. Suddenly baby takes center stage, consuming enormous amounts of the mother’s time and energy. He finds his needs are now largely ignored. Feeling rejected he is likely to withdraw, get resentful, act out, or turn to substance or process addictions to cope with the pain. The primal fears of abandonment that are wired into his brain as a result of his own unmet infancy needs have been restimulated — big time.

Meanwhile his partner may be blossoming, her needs being met like never before through her physical and emotional connection with their baby. A man can never experience the intimacy born of carrying a baby in the womb or breastfeeding. And in the early months, it can be hard for him to accept the fact that baby is more interested in mom, than in him — no matter how hard he “tries.”

She has no idea what is going on with her man, and no time to tend to him — especially as he is “acting out” in whatever way he may be doing that. Ironically, the better the mother is able to nurture her child, the more likely he will re-experience his childhood wounding because he sees even more of what he didn’t get.

MPAS is now at center stage, with neither partner having a clue what is going on. It’s not too difficult to understand then, why a man will leave, disappear — either physically or emotionally.

Much of what is understood in Attachment Parenting circles with respect to “attachment” is the vital importance of infants and children for connection. What is generally not understood is — as [John] Bowlby, the father of Attachment Theory recognized — the equally primal need of adults for connection. Neurobiology confirms it feels literally devastating on a core level to have that connection threatened.

Read about how children form secondary attachments — such as to the father — in this API article, written by Bowlby’s son.

API: How widespread is this?

MERYN: Many people are surprised to learn that in the United States, an estimated 14% of men suffer postpartum depression. During the 3- to 6-month postpartum period, the rate increases to 26%.

Factors researchers have identified as leading to male postpartum depression include dad feeling burdened at the prospect of caring for a child, burdened with the financial responsibility and missing — or essentially feeling abandoned by — their wives.

Of course, it’s the latter point that is core to MPAS. And there may be plenty for a new dad to feel rejected, abandoned or jealous about. On top of the attention and affection baby gets — that he formerly got — there’s the attention his partner is getting as the new mom, and the baby’s having near exclusive rights to his wife’s breasts.

At the same time they are feeling deprived of quality time — or any time — with their partner, most new dads at some time feel scared. Frightened that they feel helpless, frustrated even angry when the baby won’t stop crying. Frightened they’re going to repeat the mistakes made by their own father. Sleep deprived, they can’t think straight.

Of course, the new mother faces many of these issues, too, but men — especially at this time — are expected to “be strong.” On top of that, men are expected to know what to do.

None of this is to say it’s harder for dads than for moms, but that it’s hard for dads, too.

Depressed, men are likely to be irritable and aggressive. And when dads appear this way, most women will turn their focus even more toward their child. Many will be feeling they have “another baby” to take care of.

While some people argue male postpartum depression is due to the father’s feeling displaced — a “needy, greedy child” — what is not factored into the “needy, greedy” diagnosis is the attachment perspective that recognizes that our need for connection, as adults as well as children, is primal.

As a man feels himself to be not only incompetent and superfluous but also rejected and abandoned, he distances himself from home and family. It’s not that he doesn’t care, but the practicalities of “being there” are just too difficult. Many give up and leave — emotionally, if not physically.

Read this API blog post from a father about the importance — and challenge — of giving his children presence.

API: What can we do about this?

MERYN: This is a question that needs to be addressed on many levels, including and beyond the immediate family. There are a multitude of entry points to addressing MPAS.

For example, researchers have identified depression as often being the result of a dad being disabled as an involved parent, with the most depressed dads having wives who are “over-involved” with their baby. And while a growing number of men want to be more involved in caring for their children, mothers often unwittingly discourage their partner’s involvement. I found this fascinating, and I have seen it again and again, now that I am aware of it.

Men who feel supported by their wives in finding their own way of doing things are less prone to depression and develop a strong connection with their infants. We tend to overlook the fact that competency of fathering, as with mothering, is learned through the day-to-day, hands-on care of a child. This is perhaps truer today than every before, as so many of us have had very little to do with caring for the very young — unlike a generation or two ago. Yet fathers typically spend almost no time alone with their babies — not because they don’t want to, but because it’s virtually impossible for a working dad, as most dads are.

Dads need to be encouraged and supported in being key players in pregnancy and birth, and their different styles but equally significant roles as parents needs to be acknowledged — by their partners but also by pre-and perinatal providers, preschools [and other segments of society].

Read more about the father’s role in newborn parenting in this API article.

API: Can you speak a more about what you mean by multiple entry points?

MERYN: There is so much we can do. It does not need be said that being parents today is a hugely demanding endeavor that, more often than not, puts unanticipated stresses on a marriage. The more prepared a couple can be, the smoother and more joyful the transition can be.

Read about how API Leader Thiago Queiroz transitioned into his role as a new father in this API blog post, and this followup post.

Firstly, being informed about the dynamic is in itself huge. Recognize that having a baby almost inevitably puts a couple’s relationship at risk. No one can assume, “It won’t happen to us.” I would surely have been guilty of believing that.

It’s very important to recognize that fathers, too, have very legitimate and distinct concerns and needs that need to be addressed at pregnancy, birth and postpartum.

Read a father’s perspective of being his wife’s breastfeeding coach in this API article.

Recognize becoming a parent as an opportunity to heal the wounds of your own childhood. While this may be a lifelong journey, it begins with awareness and small steps. So ideally prior to conception, parents can reflect on their our own birth and childhood to identify unresolved issues that may be re-stimulated. While parents pore over books and DVDs, and attend parenting classes to learn how to care for their child, this crucial area is rarely addressed.

Read fellow Australia native Jessica Talbot’s story of healing her childhood wounds in this API article.

Recognize the significance of Attachment Theory to adult love. Recognize that adults crave and thrive on connection just as infants and children do. Reframe dad’s selfishness or immature neediness as re-stimulated unmet childhood needs for connection. And don’t rely on each other exclusively to meet those needs.

Listen to a free audio recording of this API interview with Harville Hendrix, founder of Imago Relationship Therapy — a followup of API’s Healing Childhood Wounds publication

Prepare for the postpartum period prior to the birth of a baby. Organize support — physical and emotional. Don’t try to go it alone, as we initially did.

Promote an awareness of the need for local community as well as social, economic and political policies and practices that support families — and dads. In Norway, promoting men’s early involvement with infants and children is seen as a potential tool for reducing domestic and other violence.

API: Thank you so much, Meryn, for your insights. Is there anything else you’d like share?

MERYN: People would often meet us and say, “Oh, so this is the continuum baby!” I soon learned that was so untrue that I wrote an article about it! Siena was not a continuum baby, and we could not expect to be “continuum parents.” We do not live in a continuum culture. We do not have “continuum role models.” We don’t have the village, the many hands and other supports found in those indigenous cultures. In fact, we live in a culture that diametrically opposes continuum practices — a culture that offers very little support to cooperative and collaborative living, to intimacy or to families.

Does this mean we shouldn’t even try? No! In fact I believe our well-being as a species in is large dependent on it.

An API Support Group can be a vital local resource for Attachment Parenting families looking for their support “village.”

Siena’s needs as an infant and young child were met to a degree that is unusual in this culture. And so were my needs, as a mother. However, she was also subject to our stresses and the limitations — physical, emotional and spiritual — we encountered in the absence of the village. That said, I could never conceive of parenting a child in any other way.

What I find heartening is that there are so many more resources available to parents today than a decade or two ago. At the time we purchased a baby sling, we had never as much as seen one — far less anyone wearing one. We got so many looks and comments wearing those slings. And there were virtually no continuum or Attachment Parenting groups. We formed our own in our small rural community, and it was a lifesaver. Today, you can find a multitude of blogs, Facebook groups and local [in-person] groups forming. Many of these supports today are explicitly for dads.

Unfortunately, few know about MPAS.

I imagine that many of your readers begin Attachment Parenting like we did, so full of enthusiasm. And that’s wonderful. But this needs to be tempered with the realities that we are not continuum children. We do not live in a continuum culture. I see so many parents beating

themselves up, because they [feel they] are not good enough moms or dads. I would like them not to be so hard on themselves. It’s not good for them, nor for their children. Self-acceptance and compassion for themselves in this time of huge transition is to the good of all — without exception.

I believe that everyone who is practicing Attachment Parenting to whatever degree they can, is making a difference. It’s a huge shift from the way past generations were raised — and we are really paving the way for our children, and the generations to come.

Suppressing our feelings and engaging in blame-games and power struggles take a huge toll on our energies. That said, I strongly urge couples who find they are floundering to get support — sooner rather than later. Don’t try to do this alone. Seek the support of a wise and seasoned person, a counselor or therapist.

With a whole-hearted commitment to their partnership and family, to a strong focus on working as a team, and on appreciating and supporting each other in loving and learning, a tremendous amount of energy is generated that serves both the individuals, the marriage — and the children.

*****