I am fortunate that my career allows me to work with young people promoting peace education, especially at the high school and college level. Though peace education can take place with any group or in any setting, it is often a focus in primary and secondary education. In these settings, a major emphasis is promoting emotional and social development.

David J. Smith, MS, JD, is a peacebuilding educator, trainer, and consultant. He is president of the Forage Center for Peacebuilding and Humanitarian Education, a not-for-profit that advances experiential-based humanitarian training. He is also adjunct faculty at George Mason University. He and his wife, Lena Choudhary, a nurse educator, raised their children with Attachment Parenting. Their daughter, Sonya, is a high school senior, and son, Lorenzo, is serving in the Peace Corps in Namibia. David and his family live in Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Though there is no single definition, many working in the field would say peace education aims to:

- Promote a culture where citizens understand global problems,

- Have the skills to resolve conflict constructively,

- Know and live by respecting human rights,

- Appreciate diversity, and

- Respect the integrity of the planet.

Peace education is a natural fit for those engaged in Attachment Parenting in that it centers heavily on promoting learning that is individualized and takes into consideration the learner’s learning style. It is no wonder that peace education often flourishes in Montessori education and other places where the setting is child-focused. Maria Montessori’s famous quote — “Establishing lasting peace is the work of education; all politics can do is keep us out of war” — is well known by those teaching peace education.

If you are a parent interested in understanding the theoretical dimensions of the field, I would recommend Ian Harris and Mary Lee Morrison’s Peace Education (3rd edition). Another resource is the Global Campaign for Peace Education, which is an international effort to promote the teaching of peace.

Having said this, Attachment Parenting by the nature of the approach is already engaging in peace education by emphasizing cooperation, interdependency, self-awareness, and respect for others. It is amazing how these basic notions of human relations are often missing in our society.

I’ve taught at the higher education level, especially at community colleges. I’ve also taught at liberal arts institutions and overseas in the Fulbright program. Currently, I teach at the graduate level at George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. But most of my time is spent traveling around the U.S. advancing peace and conflict resolution education. I’ve recently written a book on careers in peace for undergraduates, Peace Jobs: A Student’s Guide to Starting a Career Working for Peace.

I wanted to share 2 recent experiences I’ve had, both demonstrating the ways in which we can support young people in their aspirations for peace and a society that is violence-free:

1) Empowering High School Students to Build Peace

The Association for Conflict Resolution (ACR) is the largest association of conflict resolution practitioners and educators in the United States. I’ve been a continuous member of ACR since its formation. At its annual conference, ACR hosts a workshop for youth. For this year’s conference in Baltimore, Maryland, USA, I was invited to work with high school students. I strongly believe in youth empowerment, but more over, I’m a Baltimore native and wanted to contribute in any way I could to foster peacebuilding.

My workshop was titled “Building a Future Through Building Peace.” Working with about 40 Baltimore high school students, I engaged them in 2 activities: the first focused on having them consider their values and expectations for work; in the second, they worked in groups to consider ways to bring peace to their community.

The first activity was called “What Am I Seeking in a Career? Bingo.” Here, students worked with a bingo sheet where in the blocks I indicated a range of interests that students could engage in: “Help people in need,” “Work to end poverty and suffering,” and “Try to end violence against women” are examples. Students could ask another student only 2 questions. If the interest of the student being asked corresponded with the question asked, the student wrote their name in the box. Once the student asking the questions got 5 across, 5 down, 5 diagonal, or 4 corners and the center, they won! (I actually kept the activity going until every student had won). The objective was to get students to not only consider their own interests, but learn about other students’ interests, as well. In this way, they can find others to work with.

The first activity was called “What Am I Seeking in a Career? Bingo.” Here, students worked with a bingo sheet where in the blocks I indicated a range of interests that students could engage in: “Help people in need,” “Work to end poverty and suffering,” and “Try to end violence against women” are examples. Students could ask another student only 2 questions. If the interest of the student being asked corresponded with the question asked, the student wrote their name in the box. Once the student asking the questions got 5 across, 5 down, 5 diagonal, or 4 corners and the center, they won! (I actually kept the activity going until every student had won). The objective was to get students to not only consider their own interests, but learn about other students’ interests, as well. In this way, they can find others to work with.

The second activity was called “Peace Entrepreneur.” Here students role-played as members of a design/manufacturing company called “Make the Peace, Inc.” In teams, they were asked to come up with a product or service that might be used to increase community peace. Each team also made a poster and, at the end, gave a pitch to the other teams on their product or service. One team did their pitch in rap!

The second activity was called “Peace Entrepreneur.” Here students role-played as members of a design/manufacturing company called “Make the Peace, Inc.” In teams, they were asked to come up with a product or service that might be used to increase community peace. Each team also made a poster and, at the end, gave a pitch to the other teams on their product or service. One team did their pitch in rap!

Students often have important insight as to what their community needs. As adults, we often make assumptions that are not accurate. Young people are living day to day in communities where violence, injustice, and deprivation are the norm. Youth are also incredibly creative and can come up with ideas that will directly improve their condition. They often see the connection between peacebuilding and community wellness that adults don’t see.

The products and services that the students came up with were wide-ranging. One group recommended that a youth center would provide opportunities for young people to gather together, play sports, engage in out-of-school activities, and build community. Another team recommended a trauma-healing center. One member of that team talked about the trauma that exists in his community and how it wasn’t being addressed. Another team recommended something that I didn’t expect: making sure that all schools had air-conditioning (AC). This team argued that without AC, students are unable to feel comfortable and therefore learn. The heat creates more tension…and potentially, more violence!

As parents and educators, we must include youth in considering strategies for building peace in communities, ensuring social justice, fostering development, and overall, improving the quality of life. Adults don’t have all the answers. By working with young people, we let them know we value their insight and knowledge, thereby empowering them to make change.

2) Redesigning Peace Awareness with Younger Students

The second experience I want share took place with youth when I was visiting Penn State last spring. This was a chance to work with with elementary and middle school students, which I don’t do often. Working with this age group can be very rewarding, but also at times challenging. Developing an activity that is engaging for them, as well as meaningful from a learning standpoint can be frustrating.

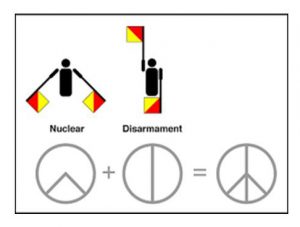

The peace sign, or symbol, is an iconic symbol that represents a variety of movements and causes.

The peace sign, or symbol, is an iconic symbol that represents a variety of movements and causes.

Michelle Rivera-Clonch, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Antioch College, wrote about the symbol in my book, providing background on the event that the symbol was created for. In 1958, an anti-nuclear protest march was planned from London to Aldermaston, England, during Easter weekend. The organizer of the march, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), was looking for a symbol that could be used to represent the march. CND approached designer Gerald Holtom who came up the symbol we know as the peace sign.

Holtom described the image as having 2 parts — first, a “little man in despair” with his arms out; second, the semaphore signal for the letters N and D, standing for Nuclear Disarmament –drawn in a circle.

Holtom described the image as having 2 parts — first, a “little man in despair” with his arms out; second, the semaphore signal for the letters N and D, standing for Nuclear Disarmament –drawn in a circle.

Because it has never been copyrighted, this symbol has been adapted and applied in a countless ways.

After a talk at Penn State, I was invited to work with a group of 5th graders at State College Friends School. I often encourage students to use their creative processes to consider their views of peace. I asked students to consider what the peace symbol might look like today if they were asked to design it. In the activity, the class was a design firm and had been asked to come up with a new peace symbol that represented today’s challenges and hopes.

After a talk at Penn State, I was invited to work with a group of 5th graders at State College Friends School. I often encourage students to use their creative processes to consider their views of peace. I asked students to consider what the peace symbol might look like today if they were asked to design it. In the activity, the class was a design firm and had been asked to come up with a new peace symbol that represented today’s challenges and hopes.

Peace Education, a Timeless Need

In the 1950s, the paramount global issue was nuclear war. Today, we are facing a myriad of challenges: global warming, extremism, domestic and gun violence, and war, to mention a few. Understandably, these are difficult issues to talk about with students, but even at the upper elementary school level, they know about the world around them.

As parents, it is not surprising that there is anxiety in considering the world that our children will enter. This can result in transferring our anxiety to our children. This is natural and probably inevitable today. But I have come to believe that by empowering with confidence-building skills and tapping their creative energy, they can and will thrive as adults and, in the process, advance values that create a safe, nurturing, sustainable, and peaceful world for all.

Further Reading:

From the “Nurturing Peace” issue of Attached Family:

From the “Nurturing Peace” issue of Attached Family:

- “Talking to Our Children About World Tragedies” by Tamara Brennan, PhD

- “Conscious Living with Lisa Reagan” (cofounder of Families for Conscious Living) interview by Attachment Parenting International