By Lysa Parker, MS, CFLE, cofounder of Attachment Parenting International, coauthor of Attached at the Heart, www.parentslifeline.com

**Reprinted with permission from Pathways to Family Wellness Magazine, www.pathwaystofamilywellness.org

It wasn’t until I became a parent that I truly understood the deep connection between early childhood experiences and how they affect our relationship to the earth and all living things. In my work with children, I found that many kids seem to have a natural affinity to nature, but this affinity must be nurtured, or it gets buried like so many other gifts.

It wasn’t until I became a parent that I truly understood the deep connection between early childhood experiences and how they affect our relationship to the earth and all living things. In my work with children, I found that many kids seem to have a natural affinity to nature, but this affinity must be nurtured, or it gets buried like so many other gifts.

When my oldest son was an infant, he was always calmest when we were outside. He could be in a full wail, but as soon as we went outside his crying stopped. To this day he loves to be outdoors, and when he feels the need to get centered and calm, he will go to his favorite place in a nature preserve or a park. There is a spiritual, unknowable, meditative energy in nature that evokes awe and reverence if we will be still, listen, and observe.

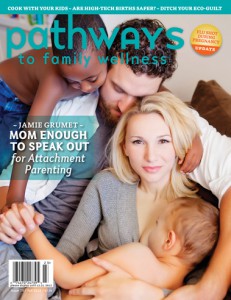

Check Out This Issue of Pathways Magazine to Get a New Perspective on TIME’s AP Coverage

Pathways to Family Wellness Magazine highlights Attachment Parenting in its newest edition featuring TIME cover mom Jamie Lynn Grumet in a real-life family portrait. This issue includes features by Jamie Lynn, API cofounders Lysa Parker and Barbara Nicholson, and other experts providing a historical perspective of the AP Movement, a biocultural anthropological overview of child-led weaning, and a discussion of the TIME cover and its cultural backlash in the context of a consciousness shift toward global wellness.

Pathways to Family Wellness Magazine highlights Attachment Parenting in its newest edition featuring TIME cover mom Jamie Lynn Grumet in a real-life family portrait. This issue includes features by Jamie Lynn, API cofounders Lysa Parker and Barbara Nicholson, and other experts providing a historical perspective of the AP Movement, a biocultural anthropological overview of child-led weaning, and a discussion of the TIME cover and its cultural backlash in the context of a consciousness shift toward global wellness.

The Man Behind a Movement

While doing research years ago for another project, I learned about the work of Dr. Albert Schweitzer (1875–1965) and his contributions to humanity. He was a theologian, medical doctor, philosopher, scholar, speaker, writer, musician, and humanitarian. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952 for building a hospital in West Africa and devoting his life to treating the people there, who suffered from disease, famine, and the ravages of war.

As I was doing research for this article, about the relationship between Attachment Parenting and the environmental movement, I kept coming back to Dr. Schweitzer’s work. He is best known for creating an ethical philosophy in 1915 called “Reverence for Life,” a philosophy that he considered the basis for morality, which he referred to as a universal principle of ethics. In his 1923 treatise, Civilization and Ethics, Schweitzer wrote: “Ethics is nothing other than Reverence for Life. Reverence for Life affords me my fundamental principle of morality, namely, that good consists in maintaining, assisting, and enhancing life, and to destroy, to harm, or to hinder life is evil.”

According to The Albert Schweitzer Fellowship website, Dr. Schweitzer stressed “the interdependence and unity of all life,” and is considered by many to be the forerunner of the Environmental and Animal Welfare movements. In 1962, author Rachel Carson dedicated her revolutionary book, Silent Spring, which ignited the environmental movement, to Dr. Schweitzer.

The Reverence for Life ethic may seem obvious to those who have highly developed capacities of empathy and compassion for all living things; for others, it takes an awakening of conscience, with some re-educating about how our actions impact living systems. The family system is one that has been neglected for too long and is our only hope for future generations, so we have to view all living systems as integral parts of the whole. What we do, how we interact with each other, and what we teach our children will determine how they treat others and engage in the world. Being the quintessential observer and philosopher that he was, Dr. Schweitzer understood this well and addressed the importance of teaching children, stating: “Adults teach children in three important ways: The first is by example, the second is by example, and the third is by example.”

“As the middle child of five born to a hard-working father and a stay-at-home mom, the main tenets to maintain sanity and stability were practicality and resourcefulness. There was always a purpose behind our collection of four-legged friends. We raised sheep, rabbits, ducks, and a goose. Each of the children had husbandry chores in addition to household responsibilities. Mother always had a large garden. I have very fond memories of the apple cider assembly line production in the front yard. Mom and Dad still have the apple press in their kitchen, albeit as an ode to the past. A lot more time was spent harvesting food at home than time spent grocery shopping, or any type of shopping; mom sewed, and the clothes moved from one child to the next. With four girls, this was a cost-effective approach. When I recently decided to start our gentleman’s farm (three Nigerian dwarf goats, six free-range chickens, two dogs, and a cat), it was to recreate that synergy for my son, which had developed in me a strong work ethic and a great appreciation and respect for nature’s generosity.” ~ Cathleen K.

Attachment Parenting

Someone said, “When you change the way you view the world, the way you view the world will change.” That’s what happened to me 30-odd years ago when I became pregnant and read Suzanne Arms’s book, Immaculate Deception: My world view changed and the activist in me was born. I was later introduced to the breastfeeding and Attachment Parenting world through La Leche League meetings in Nashville, Tennessee, USA, where I discovered my passion and mission in life, to advocate for children and their families.

Initially, my journey into Attachment Parenting was one of trepidation, because I didn’t know anyone who had older children that had actually parented this way. With the support and experience of other mothers at the meetings, and watching them interact with their children so lovingly and respectfully, I couldn’t resist my awakening intuition that told me it was right.

“In general, my daughter has less stuff because we followed some attachment principles. We didn’t buy things like a baby monitor, a play gym, a baby bathtub, pacifiers, mobiles, or most things meant to soothe or occupy a baby. We kept her close, and her entertainment was whatever we were doing.” ~ Carrie N.

At one meeting, I met Barbara Nicholson, and we became lifelong friends and sisters in this journey ever since.

In the early 1990s, we learned that many Attachment Parenting groups were popping up across the country, but there was no distinct or cohesive movement or clarity about what this new phenomenon actually was. Everyone seemed to have their own interpretation. The term “attachment parenting” (AP) was coined by Dr. William and Martha Sears, and was defined by the principles they called the “Baby Bs” as a way of helping parents learn to empathize and become more attuned to their infants. (These included “birth bonding,” “breastfeeding,” and “belief in a baby’s cry.”) Their books were our lifeline, because no other pediatricians, let alone mainstream society, were supporting our choices.

As educators, we saw the disconnection of our students due to dysfunction in their homes, and we felt strongly that it was due in large part to parents not having accurate parenting information or support. In 1994, Barbara and I formed our grassroots, nonprofit organization, Attachment Parenting International (API), to provide parents with the evidence-based information they need to debunk the bad advice of many popular parenting books (some still popular today), and created parent support groups around the country and internationally.

At that time, many AP families were also involved in the Environmental Movement, but we knew that we had to keep our message simple and focused strictly on principles related to the parent-child attachment relationship, just as La Leche League International later decided it had to focus on breastfeeding rather than parenting. It didn’t mean that we didn’t value or appreciate natural living lifestyles, just that we knew we had all we could handle in terms of promoting the attachment message. We also understood that if we could help parents raise empathic children, then that empathy would carry over in all aspects of life.

Some felt that the Searses had created a parenting formula, but what they really taught us was to trust our intuition and the reasons why this empathic style of parenting was so critical to children, the family, and society. Their overarching message helped us learn to respect and trust our baby’s cues and our own instincts; the baby will tell the parent what she needs through her body language and cries, and the parent’s sensitive response to her cues will teach her the first lessons of trust. And that was just the beginning.

“I was already very involved in the environmental movement before I had children and had learned not to accept things at face value and consider what is truly best for families and the earth. So when I had children, attachment parenting was a natural fit. It is more about connection and less about material things. Now our eight-year-old son is helping our family with recycling, gardening and composting. I also homeschool using Waldorf methods and philosophy, which is all about inculcating reverence for life, and I think that really helps, too.” ~ Kara C.

Creating a Conscience

The Searses have long taught that when we see the world through our children’s eyes, our worldview changes. We begin to feel more respect and empathy for our children’s feelings, and act accordingly. The way we are treated as children and the example our parents set for us are the primary determining factors in developing a conscience.

Every child’s brain has the capacity to develop empathy, compassion and remorse, all of which comprise the inner workings of the conscience. The brain is a “use it or lose it” organ, so the window of opportunity to develop these capacities is in the early years of a child’s life. These early experiences don’t rest solely on our interpersonal relationship, but also in what we are taught about our relationship with the external environment—teaching the value of and expressing appreciation for the natural world.

“Compassion, in which all ethics must take root, can only attain its full breadth and depth if it embraces all living creatures and does not limit itself to mankind.” ~ Dr. Albert Schweitzer

Parenting for a Sustainable World

With the Searses’ permission, API expanded on the Baby Bs to create The Eight Principles of Parenting. These are intended to provide guidance for the optimal development of children that we can strive for, but they are not intended to be standards of perfection. They can be used as core principles, regardless of what name is used for the parenting style: Attachment Parenting, natural parenting, conscious parenting, or original parenting. API recognizes that there are many configurations to what constitutes a family and, depending on their life circumstances, parents are encouraged to use what works in their family and leave the rest.

With the Reverence of Life ethic in mind, these Eight Principles are designed to be respectful of the needs of the newborn child who comes into this world with a set of expectations: to be held, fed, protected, and loved in a multi-sensory bath of smells, touch, and loving words. There is an intimate connection, also known as attunement, that arises out of the day-to-day care to the point where the mother or primary caregiver can begin to intuit what the child is feeling and what his needs are before the child has words to express himself.

The principles themselves are based on respecting the natural systems–the less interference, the better. For example, “Feed with Love and Respect” encourages breastfeeding as the ideal attachment model: It’s natural, it’s designed for the human infant, there’s no waste, and there is respect for the hunger cues of the infant, rather than adhering to rigid schedules. In environmental terms, it is a natural, closed-loop system that has a natural flow or rhythm.

With slight adaptations, the principles can easily be adapted for older children as well.

- Prepare for Parenting: Become knowledgeable about your child’s emotional, developmental and cognitive levels.

- Respond with Sensitivity: Stay emotionally responsive.

- Feed with Love and Respect: Strive for optimum physical health.

- Use Nurturing Touch: Maintain a high-touch relationship with your child.

- Engage in Nighttime Parenting: Develop and maintain positive sleep routines.

- Provide Consistent, Loving Care: Be physically present and emotionally available for your children.

- Practice Positive Discipline: Preserve the connection with your child.

- Strive for Balance in Your Personal and Family Life: Navigate the challenges of modern society.

“Becoming pregnant was akin to opening the floodgates: My intuition increased tenfold, my artistic juices overflowed. I was genuinely fascinated with the evolution of pregnancy, and invited a community of friends and family into the delivery room to welcome Jackson into each daily adventure. The tenets of Attachment Parenting make complete sense to me. Even though I was introduced to the work after Jackson was born, I had already embodied much of the ideology. I consider parenthood a privilege and a responsibility. I think of motherhood as the invitation to create, contain, and let go. I cherish every cuddle, knowing a self-possessed nine-year-old is around the corner, and then I will have to be satisfied with hurried pats on the back. Why rush it? I have surrendered my ideas of how I thought it would/should be and accepted the messes and the madness. I do pick my battles—holding strong on ritual (family dinners and reading books before bedtime) and respect for the adult and the child. It’s amazing what we hear when we really listen. If I’m consistent, he will be too. I may be raising an only child, but I am clear that how I treat him will affect how he treats others throughout his life, including his own family.” ~ Cathleen K.

Parenting and Permaculture

There are a multitude of similarities between Attachment Parenting and the Green Movement, particularly the Permaculture Movement. Sometimes parents are attracted to Attachment Parenting, because it already fits their lifestyle and philosophy. More often, parents find Attachment Parenting, because they are looking for a better way of raising children, and as a result find their own consciousness awakened, realizing that their children present a greater purpose for society, and as such, feel more obligated to teach them to be good and compassionate stewards of the earth.

The concept of permaculture can be difficult to define. Some describe it as “a connecting system between disciplines,” or “observing nature and the natural flow of systems.” Permaculture ideally is “a closed-loop system, taking responsibility and producing no waste.” Many AP parents consciously choose to take responsibility to minimize material things that create waste.

David Holmgren, one of the originators of the permaculture movement, helped to create 3 Permaculture Ethics and 12 Principles as the framework that can be applied in ecosystems, businesses, communities, and the nation. I would add families to that list.

The 3 Ethics are:

- Care of the Earth

- Care of People

- Fair Share (for everyone)

The 12 Principles are:

- Observe and interact

- Catch and store energy

- Obtain a yield

- Apply self-regulation and accept feedback

- Use and value renewable resources and services

- Produce no waste

- Design from patterns and details

- Integrate rather than segregate

- Use small and slow solutions

- Use and value diversity

- Use edges and value the marginal

- Creatively use and respond to change

To learn more about the 12 principles, go to www.permacultureprinciples.com/freedownloads.php.

In Australian, filmmaker Peter Downey’s film Anima Mundi, collective voices speak of the urgent need to help the earth achieve balance—that we must “evolve or perish, grow up or die,” because, like it or not, the world is changing. As we witness various groups and politicians point fingers of blame, our reality remains the same: Our populations continue to increase, while our resources dwindle away and the climate continues to change. We can and must raise new generations of children who will become adults who are conscious, concerned and committed to helping heal the earth. Attachment parenting families are doing just that.

As humanity slowly comes to the realization of the damage we have done to this living organism we call earth, we have learned some hard lessons along the way. We must take personal responsibility, and teach our children well.

“I think it’s because we are very mindful of our choices. Just as we care for our children by making decisions to do everything in their best interests (whether that’s babywearing, cloth diapers/wipes, organic foods, etc.), we extend that same mindfulness and respect to others in our families, neighborhoods, and environment. I think because Attachment Parenting has such a core value of respect, we don’t only respect our children, but also everyone around us. We want the earth to be a good, clean, and healthy place for our children to grow up, and for everyone else’s children, too.” ~ Jennifer Y.