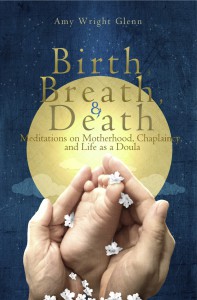

An interview with author Amy Wright Glenn about her book Birth, Breath, and Death: Meditations on Motherhood, Chaplaincy, and Life as a Doula.

Tell us about your book.

Birth, Breath, and Death: Meditations on Motherhood, Chaplaincy, and Life as a Doula is a heartfelt account of my work with the birthing and dying. I am a doula. I hold space for women as they give birth. I am a chaplain. I hold space for the dying. I am drawn to life’s thresholds. I am drawn to these doorways.

Birth, Breath, and Death is also a deeply personal exploration of what it meant for me to become a mother, given the painful legacy of my mother’s mental illness. I write about the healing attachment found in cosleeping, breastfeeding and babywearing. I weave together research on attachment and brain development, with reflections on empathy and compassion.

Finally, I share personal stories about birth and death, combined with philosophical reflections as my academic background is in the study of comparative religions and philosophy.

What inspired you to write this book?

My husband, Clark, came up with the title of this book during my training as a hospital chaplain. However, I wasn’t ready to write this book at that point in my life. It was the birth of my son–and the subsequently profound opening of my heart–that compelled me to write this book.

I didn’t want to go back to full-time academic work after holding my newborn in my arms. I knew I could use my skill as a writer to contribute financially to the family and fulfill my heart’s longing, and the longing of my young son, to stay at home and nurture him with the best of my energy and talents.

Much of Birth, Breath, and Death came to me in meditation, and I often woke up from sleep with sentences running through my mind. Writing has opened up many doors for me, and I’m grateful to find a way to work from home and share my insights, struggles, hopes and experiences.

How will this book benefit families?

All of us are born. All of us die. I write about the deepest questions we can examine in life. Within our family circles, we encounter both the miraculous and the mundane. Within our families, we most deeply encounter the transformative energies of birth and death.

I believe we all benefit from reflecting upon what it means to be born and what it means to die. These are life’s big questions. Even if one disagrees with my responses to these big questions, it is still invaluable to take the time to reflect upon them with an open heart and mind.

Parents, in particular, will benefit from reading this book as I reflect on what it means to be a parent and find one’s own way, trust one’s intuition, and draw upon best practices and scholarship to bring out the best in oneself and one’s children.

You share birth stories and reflect upon your work as a chaplain supporting the dying, but tell us more about the “Breath” part of your book.

The first thing we do upon leaving our mother’s body is breathe in, and the last thing we do before we die is breathe out. The breath is the link, the thread. It is a powerfully loyal friend throughout life’s journey between birth and death.

I practice meditation and teach yoga. Conscious breath awareness is central to these mindfulness practices. It’s central to living a mindful life. The “breath” part of the book relates to teachings drawn from many wisdom traditions that help us keep our hearts open as we live with love and seek truth.

You studied comparative religion and taught this on the college and high school level, so how does this impact your writing?

My studies of comparative religion and philosophy profoundly impact everything I do. I love making links between the particular and the universal, between the day-to-day patterns of living and the deep reflections that thinkers across time and culture bring to human life. My book is academically rigorous in the sense that I draw freely from my training as a scholar in the telling of birth, breath and death tales.

What are your views of Attachment Parenting International and what API is doing? How does your book work within our mission statement?

Attachment Parenting International is an organization I admire, support and celebrate. I’m very grateful for API’s commitment to link best parenting practices with research, and support families to develop secure attachments that foster the development of empathy, courage and resilience.

I found myself naturally practicing many AP styles of mothering and applied my previous research in the field of ethical development to the work of nurturing my son. I certainly want to support all parents to “raise secure, joyful, and empathetic children.” We do this best when we as parents embody these qualities ourselves.

My book chronicles my own journey of working through the pain of a difficult childhood and emerging with joy and empathy to embrace openhearted mothering.

Where can readers find more information?

Readers can visit my website www.birthbreathanddeath.com to read reviews of the book and find purchase information.

In April 2005, Rani Jamieson gave birth to a healthy baby boy, Tariq. She was given Tylenol #3, a medication containing acetaminophen and codeine, for postpartum pain. She took two pills twice a day, less than the prescribed amount, and cut this dose in half two days later after experiencing fatigue and constipation. She was told it was safe to take this medication while breastfeeding, and did so.

In April 2005, Rani Jamieson gave birth to a healthy baby boy, Tariq. She was given Tylenol #3, a medication containing acetaminophen and codeine, for postpartum pain. She took two pills twice a day, less than the prescribed amount, and cut this dose in half two days later after experiencing fatigue and constipation. She was told it was safe to take this medication while breastfeeding, and did so.