By Lisa Lord, editor of The Attached Family.com.

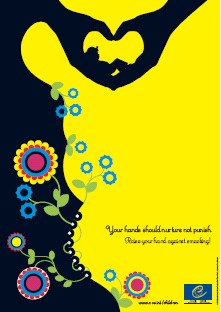

Though research continues to show that spanking and other forms of physical punishment are both ineffective and harmful, and despite many nations across the globe instituting bans on corporal punishment in schools and homes, the laws of the United States still do not reflect this reality. Corporal punishment teaches children that violence is a way to solve problems. Children worried about being paddled are not free to learn. And according to The Center for Effective Discipline (CED), certain groups–poor children, minorities, children with disabilities and boys–are hit in schools up to 2-5 times more often than other children. Nadine Block, cofounder of the CED and SpankOut Day April 30, is committed to changing this for American children and children everywhere.

Though research continues to show that spanking and other forms of physical punishment are both ineffective and harmful, and despite many nations across the globe instituting bans on corporal punishment in schools and homes, the laws of the United States still do not reflect this reality. Corporal punishment teaches children that violence is a way to solve problems. Children worried about being paddled are not free to learn. And according to The Center for Effective Discipline (CED), certain groups–poor children, minorities, children with disabilities and boys–are hit in schools up to 2-5 times more often than other children. Nadine Block, cofounder of the CED and SpankOut Day April 30, is committed to changing this for American children and children everywhere.

Block spearheaded the advocacy movement in Ohio, USA, that resulted in a legislative ban on school corporal punishment in that state in 2009. In her latest book, Breaking the Paddle: Ending School Corporal Punishment, Block shares her experience and wisdom to inspire others to join the movement to end corporal punishment of children, and to give them the tools to make it happen.

It was enlightening and inspiring to talk with her about what advocates have been able to achieve thus far, how much farther we all have to go to see the end of child corporal punishment and how the United States compares to other nations when it comes to legally-sanctioned physical punishment of children.

LISA: Tell us about your new book Breaking the Paddle: Ending School Corporal Punishment. What inspired you to write this?

NADINE: I wanted to bring attention to the existence of the practice, because over 200,000 children in 19 states are still being permitted to be hit for misbehavior. This is shameful and unnecessary—and a lot of people don’t know it’s still going on.

I also want to give people tools to protect their children as much as possible if their school districts still permit corporal punishment, and to help end it for all children. It is not enough to say, “No paddling.” You have to show people how it can be ended and encourage them to do so. My experience of more than 25 years of working at all levels–local, state and federal–gives me a unique perspective to be able to do that. About 70 percent of adults in surveys say we should ban it, so I wonder where is the tipping point? When can we get this done?

LISA: How do you feel about the U.S. status globally on the topic of corporal punishment of children?

NADINE: I am embarrassed that we are the only country other than Somalia that has not signed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which provides for giving children basic human rights including protection from harm. I am embarrassed that over 100 countries have banned corporal punishment in schools and that 36 have banned it in all settings, even homes, but we allow it in schools in 19 states and in homes in every state.

LISA: As a parent, the thought that someone else would be legally allowed to hit my child is shocking.

NADINE: In some school districts, parents have no right to disagree or to prevent this. In those cases, we tell the parents to write a letter stating that under no condition should their child be hit, and if the school needs help disciplining the child, then the parent will come to school and meet with the staff. Then the parent should sign and date the letter and try to have the child’s pediatrician sign as well. I’ve found that most school districts would be hesitant to hit that child, because the parents have said unequivocally not to.

LISA: You worked as a school psychologist and saw the effects of corporal punishment firsthand. You said in a previous interview with API, “One cannot study learning and behavior without becoming opposed to physical punishment of children. It is harmful and ineffective in the long term.” What kinds of effects on learning and psychological well-being have you seen?

NADINE: We know that people learn best in a more nurturing environment. It is hard to learn when fear is a motivator. Kids may also become school resistant and not want to go to school, and part of the reason is fear of getting paddled, especially for sensitive children who are hurt by even seeing someone else paddled. In my book, I have an example of a reading teacher who tells how kids would come into her reading group anxious and worried, either because they would be hit when they got back to the classroom for something they did, or because of something they saw.

It is not a way to teach children to be independent. What does this teach them about [what to do] when the punisher isn’t nearby? This is not what we want for the long term. We want people who are independent and know that following rules is good for them and the country and their family, not just to escape punishment.

LISA: Why do you think that policymakers ignore research when it so plainly spells out the risks of corporal punishment on children? Who is opposing ending corporal punishment in schools?

NADINE: A lot of it is regional. There are areas of the country, particularly the South and rural areas, where people tend to be more supportive of the use of corporal punishment and do not want it to be interfered with. Some have not fully examined it and give a knee-jerk response. It’s a very emotional issue for them. To question the use of corporal punishment is to question the parenting they had, the parenting they are giving and authority in general.

I believe it shows a fear of losing authority. They look through a prism of tradition, order and faith [religion]. They believe that parents are losing authority and children are worse than ever before in history. They do not believe the statistics that show young people today are less violent, have fewer out-of-wedlock babies, and do less drugs and drinking. They read about a few bad apples and extrapolate that to a whole population.

LISA: What is your strategy when you meet this kind of resistance?

NADINE: The first thing to realize is that social change is slow, but people do change over time. If they hear a message over and over again, they tend to come around. You have to be temperate, consistent and persistent. You may move people, but it may not happen quickly.

In the beginning, it was difficult because I thought that bringing research and reasoned arguments would change hearts and minds. I learned it is much more difficult. You have to appeal to emotions, too, such as with stories about children who are injured. You have to be consistent and temperate in response to critics, who are often quite angry. We move slowly in protecting children but have not gone backward. Knowing you are on the winning side makes advocacy much easier.

If you can get people in the community or the church to come on the side [of opposing corporal punishment], it’s easier. For example, when I found that several African American school board members supported corporal punishment and didn’t want it taken out of schools, Dr. Alvin Poussaint and I asked 20 national African American leaders–including the Reverend Jesse Jackson, Sr., and Marian Wright Edelman [founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund]–to sign a proclamation calling for an immediate ban on corporal punishment in schools. Having that proclamation come from inside was helpful.

LISA: If you are from one of the states that doesn’t allow corporal punishment, then it might not be on your radar screen at all.

NADINE: Right. I think that people from the North, such as New Jersey, where corporal punishment has been banned a long time, need to start moving toward the more European model, which is to ban it in all settings, like 36 countries have done. We can do that incrementally, if necessary, like not allowing the use of instruments to beat children or not allowing children with disabilities to be hit. Protecting children still needs to be on the radar.

There have been a few bills in states like Massachusetts where they have tried to do that. But they will have to try more than once to educate people about why this is needed. It’s so much easier to kill bills in legislature than to pass them.

LISA: In a part of your book, you mention that most educators are not sadists, but they are using the paddling because that is all that is promoted at the school for discipline. Perhaps you can recommend some great positive discipline programs for schools that want to consider transitioning from corporal punishment?

NADINE: Our education goal is to improve instruction and behavior for all students. We want to have caring, informed, empathic, productive citizens. It means using misbehavior as an opportunity for teaching rather than just punishing. It means recognizing that most misbehavior is a mistake in judgment. It means thinking about what we, as adults, want to happen when we make mistakes. We want to learn from them, not be hit for them. It means teaching children social skills they need to behave appropriately, such as listening, asking questions politely, cooperation, managing anger and disagreement, and sharing.

The successful programs are data based and provide a decision-making framework that supports good practices every day throughout the district. Many school districts use Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS). It is a U.S. Department of Education system-wide effort that involves using data for decision making, defining measurable outcomes that can be evaluated and supported, and implementing evidence-based practices that can be used for prevention. So instead of punishing kids for specific things, it looks at what we are punishing kids for–perhaps tardiness or fighting in the halls, for example–collecting data so that we know what needs to be changed, then looking at preventive practices that could be used decrease the problems. (See the CED’s website for more information about positive discipline programs.)

In school districts, there is either an atmosphere of looking at things to punish or looking for a way to solve problems. I’d rather be in a district looking for ways to solve problems.

LISA: How can parents and professions start an advocacy effort and locate like-minded policy lawmakers to join them?

NADINE: Advocates for bans should check the list of national organizations that have positions against school corporal punishment. There are more than 50 of them on the CED website.

Start by gathering a support group. At the state level, work on those organizations that already have positions against corporal punishment. Get them to sign a proclamation calling on the state legislature to ban it. Having a long list of organizations shows support for a ban.

Locally look at the organizations that have positions against corporal punishment and find members in the community, such as PTA members, psychologists and mental health professionals, and physicians, especially pediatricians and ER [emergency room] doctors who see paddling injuries. Parents who have had children injured often make wonderful supporters.

Keep informed by reading stories about corporal punishment and doing research on its effects. Join organizations like The Center for Effective Discipline. Help start or join organizations seeking bans in your state. (The CED can help identify these.)

As for lawmakers, take a look at their websites. What bills have they introduced? What is their background? For example, Governor Ted Strickland was a compassionate psychologist prior to becoming a legislator, and he was instrumental in getting a ban in Ohio schools. If you are trying to change a school district policy, attend a board of education meeting. You can tell a lot about the board members by questions they ask, their empathy for children and parents, and their responses.

This is what I did in Ohio. The states around Ohio, like Kentucky and Indiana, still have corporal punishment, but we don’t because we worked at it.

LISA: What effect do you hope your book will have on society?

NADINE: First I want to say corporal punishment in schools is still going on. It isn’t appropriate, and we need to change it. Also I want to tell people how they can do this, to give them the tools and the process they need to go through.

If you take on something like this, you will meet wonderful people, you will feel good about helping children, and you will teach them that giving back is so important. You get so much more back than you ever put in. No state has ever rescinded laws in corporal punishment in schools. Some people have tried, but it has never happened. This is a winning-side argument—and it is a great side to be on. It is the winning side of history.

Visit the Center for Effective Discipline (www.stophitting.com) for information and resources including effective discipline at home, successful positive discipline programs for schools, tools for advocacy efforts, and the latest news from the CED.

response to an article published on The Attached Family on July 28, 2009,

response to an article published on The Attached Family on July 28, 2009,  The Council of Europe wants a continent free of corporal punishment. Hitting people is wrong — and children are people, too.

The Council of Europe wants a continent free of corporal punishment. Hitting people is wrong — and children are people, too. Adverse experiences early in life can lead to minor childhood behavior problems, which can grow into serious acts of teen violence, according to new research. This “cascading effect” of repeated negative incidents and behaviors is the focus of an article in the November/December 2008 edition of Child Development.

Adverse experiences early in life can lead to minor childhood behavior problems, which can grow into serious acts of teen violence, according to new research. This “cascading effect” of repeated negative incidents and behaviors is the focus of an article in the November/December 2008 edition of Child Development.